How a novel buy-back model could transform the steel circular economy ~

Although the industry calls it scrap, steel is a valuable resource as a secondary raw material. Whether it’s the steel contained in products at the end of their useful life, or the material left over from the manufacturing process, there’s more industry can do to reduce its reliance on virgin raw material. Here, Advanced Engineering UK interviews Mats W Lundberg, sustainable business manager at Sandvik Materials Technology.

Advanced Engineering (AE): What is Sandvik’s buy-back programme?

Mats W Lundberg (MWL): It’s a project where we’re offering to buy-back the high alloy steel from our customers at the end of the product lifecycle. In the first instance, we worked with one of our customers, Stamicarbon, a specialist in the urea fertilizer sector, to decommission an old heat exchanger in one of its customer’s plants, which we then used as a secondary raw material in our premium steel-making process.

We can also buy-back the scrap that’s produced during the manufacturing process. For example, a manufacturer of knives and razor blades that uses a stamp pressing process on sheet metal, will have scrap metal that goes into a scrap bin at the end of the production line. We can buy-back this material and recycle it to make high-grade steel.

AE: What problem does it solve?

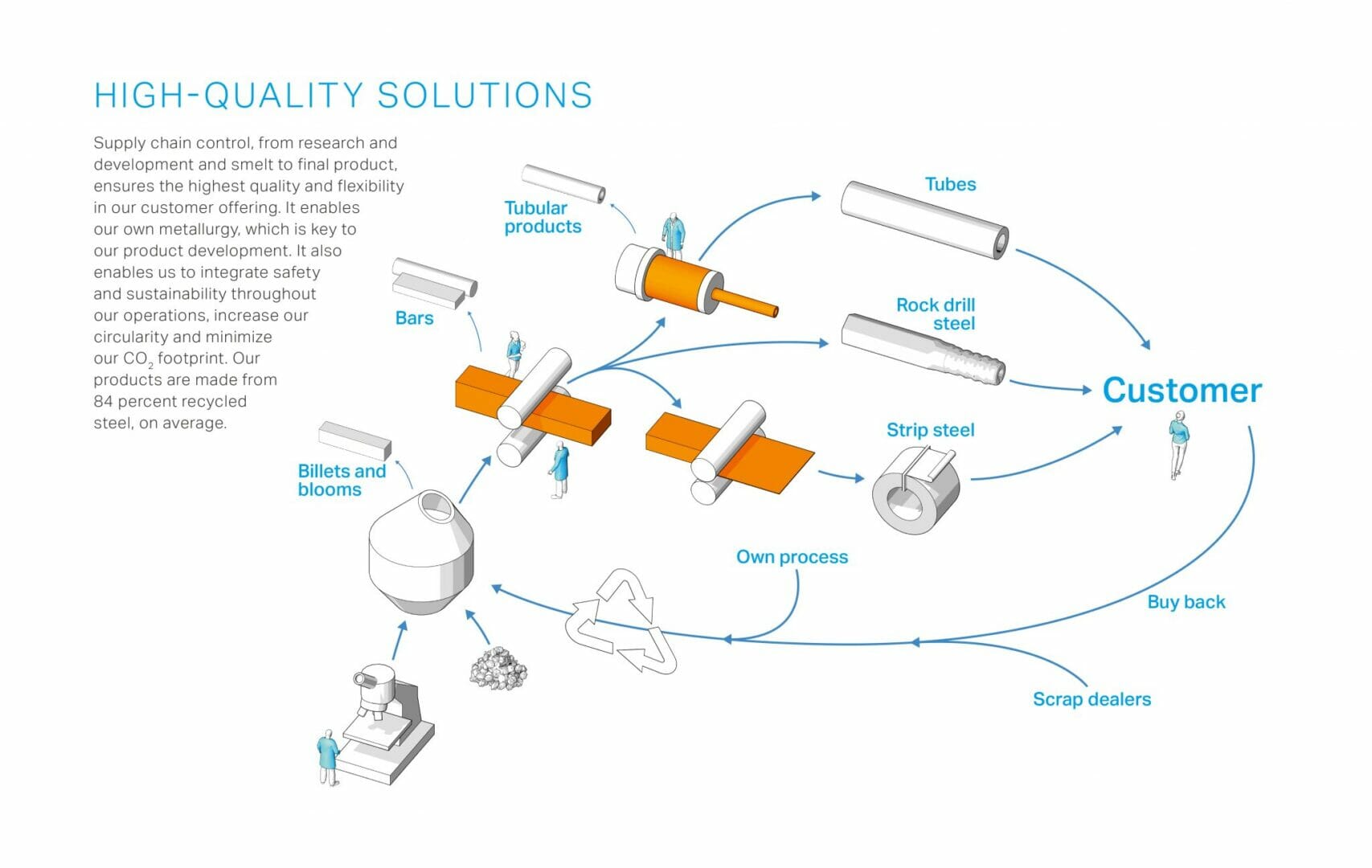

MWL: Traditionally, when plant equipment made from steel reaches its end of life — or with the scrap that’s left over from production — manufacturers find a scrap dealer to dispose of the steel.

The scrap dealer collects the various steels and sorts it in categories based on content, which is then sold back to industry. The problem is that the sorting is not always perfect and similar steel grades are often mixed together. This downcycles the quality of the steel when reusing it as a secondary raw material to create a premium steel. It also means, the manufacturer must add virgin materials to get the right composition when creating a specific steel grade, which perpetuates a non-sustainable supply chain.

With this buy-back scheme we know the exact quality of the steel because we supplied it in the first place. This means we know its make-up in terms of the content of alloyants, for example such as nickel, chromium and molybdenum. As a result, we will be closer to the desired content in secondary raw material in the melting stage. Crucially, it means we can use a higher quantity of secondary raw material and less virgin material.

AE: What are the benefits of this model?

MWL: For manufacturers it’s more economical to have a buy-back clause in their supply contract, so they don’t have to deal with the decommissioning of their parts and sourcing a scrap dealer — instead, they have a guaranteed buy-back at the outset and it also means they can promote their use of recycled material in a circular way.

Across the European steel industry, steel is typically made up of around 50 per cent recycled material, the rest is virgin raw material. At Sandvik, our steel is made up of around 82 per cent secondary raw material, and we have a goal to reach 90 per cent by 2030. For premium steel manufacturers such as ourselves, it means we can use an even higher quantity of recycled material in our process, reducing our reliance on virgin raw material and at the same time become even more sustainable.

AE: What does the future hold for this circular model and what challenges does industry face before it can adopt it more widely?

MWL: One challenge is to do with carbon miles. While we want to be able to buy-back material from our customers, it’s not always environmentally beneficial or economical to ship back every steel grade that we’ve sent from Sweden across the world. Developing partnerships with steel manufacturers in the local country to feed back into the regional supply chain could be one way of addressing it.

To ensure the model works, we’ll need to also adapt cross-company workflows to ensure that scrap of different grades doesn’t get mixed before our customers ship it back to us and that we know the content of all the steel we buy-back. For example, steel with a high molybdenum content is useful for applications that require corrosion resistance or high-temperature resistance, but can make the steel more brittle at lower temperatures. So, it will be essential to ensure traceability through the buy-back process.

In the future, the model may be expanded to allow manufacturers to only pay for the steel they use, and even models where customers pay on a monthly subscription for finished steel parts such as the tubes used in a heat exchanger.

Above all, however, schemes like this will help to make the steel industry more sustainable, using a circular economy to ensure that we maximise the usefulness of the valuable raw materials we have available to us.

The development and application of advanced metals remains vital to all advanced manufacturing sectors, especially aerospace and automotive. Performance Metals Engineering, one of six show zones at Advanced Engineering UK, specifically provides the latest business opportunities and developments in design, processing & production. Find out more here.